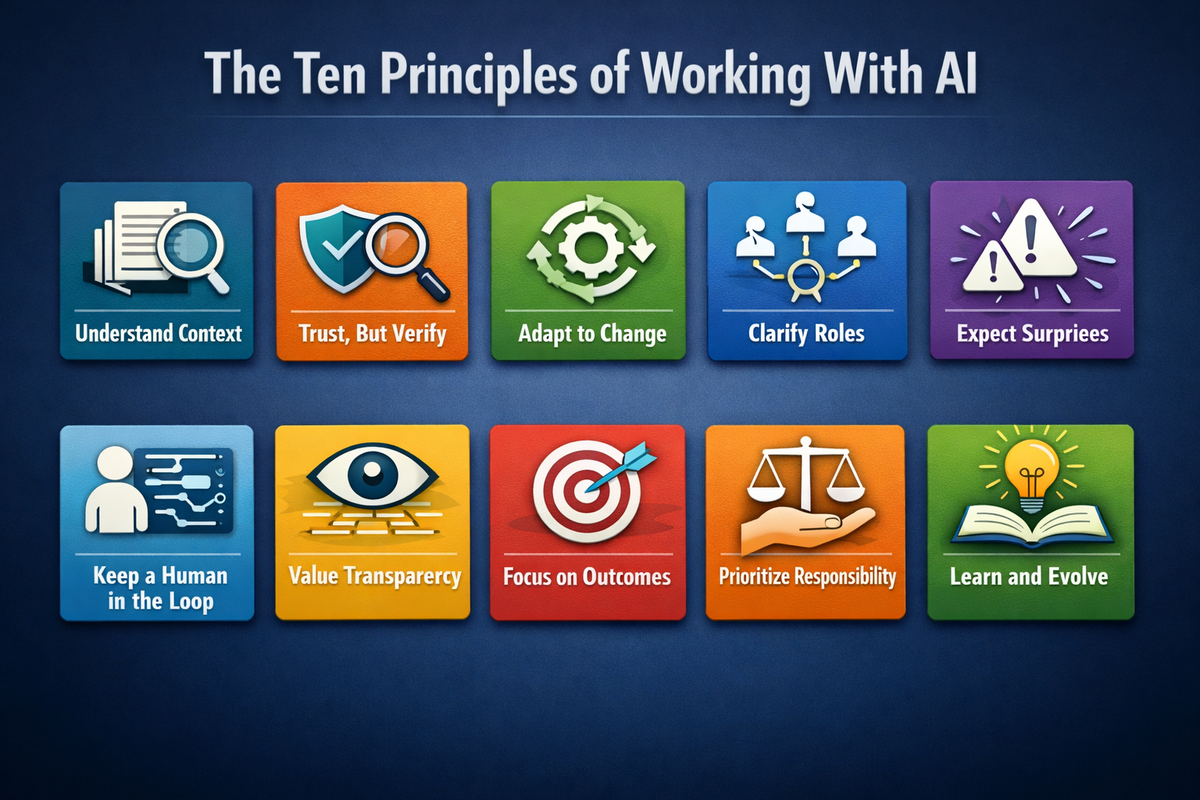

The Ten Principles for Working With AI

AI has shifted from a tool we pick up to an environment we work inside. This article introduces ten practical principles that clarify how these systems behave, where responsibility remains human, and how to stay oriented as scale, speed, and confidence outpace judgment.

Over the next week or so, I'll be publishing a series examining the ten principles of working with AI—a framework inspired by Christopher Mims' practical synthesis in How to AI. Each piece will focus on a single principle, beginning with a failure mode that actually happens when these systems are deployed without reflection, then examining what that pattern reveals about where human responsibility still matters. The goal isn't to theorize about what AI might become or to offer another set of best practices that will age poorly. It's something more modest: to surface the implicit rules that already govern how we interact with these systems, before those rules surface themselves through consequences we'd rather avoid.

Why principles, and why now

Artificial intelligence arrived in most organizations first as a tool, then as a curiosity people passed around in meetings, and eventually as a set of promises about what the future might hold. Increasingly, though, it has become something harder to pin down—more like an environmental condition than a discrete technology. You find it embedded in software you already use, woven into workflows you didn't design, shaping interfaces and decision pipelines and the media that flows through your feeds, often without anyone being able to point to a specific moment when it was adopted or a clear decision that put it there.

This shift creates a genuine problem of orientation, one that most people and organizations haven't fully reckoned with yet.

When a technology starts behaving less like an instrument you pick up and put down and more like an ambient system that surrounds your work, operational guidance by itself stops being adequate. Instructions go stale faster than anyone can update them. Best practices that worked six months ago fragment and contradict each other. Explanations tied to specific products fail to generalize to the next product, or even to the next version of the same product. What remains genuinely useful in this environment are principles—stable reference points that describe how these systems actually behave once they're embedded in the messy reality of human activity.

The principles laid out in this series aren't abstract claims about the nature of intelligence, and they're not a theory of mind dressed up in practical language. They're not a manifesto about automation or a prediction about where all this is heading. They are, more modestly, principles for working with AI—which is to say, principles that govern how interaction happens, where responsibility actually lands, and what practice looks like when you take the technology seriously.

They're worth adopting because they hold up under pressure.

From tools to systems of behavior

A spreadsheet is a tool in the straightforward sense—you open it, you do something with it, you close it. A compiler works the same way. Even a search engine, for most of its history, behaved like a tool: you asked it something, it retrieved results, and the transaction was complete.

Generative and predictive AI systems behave in a fundamentally different way. They respond probabilistically rather than deterministically. They adapt to context in ways that can be difficult to predict or even to notice. They produce outputs that carry the appearance of intention without being grounded in anything we would recognize as intent. And they operate across domains rather than staying neatly within one—the same underlying system might write your marketing copy, analyze your spreadsheet, and draft your legal brief.

Because of this, many of the failures people attribute to AI aren't really technical failures at all. They're failures of framing, of expectation, of delegation. The systems do exactly what they're structurally set up to do; when the outcomes surprise us or disappoint us, it's usually because the structure was implicit rather than designed, assumed rather than examined.

Principles exist to make that structure explicit before the surprises arrive.

Why these principles are not about correctness

The principles introduced here are drawn from the practical synthesis that Christopher Mims has articulated in his work on artificial intelligence, particularly in his book How to AI. The intent isn't to improve on that synthesis, or to revise it, or to mount some kind of challenge to it. The intent is to adopt it as a stable foundation and then to work outward from there.

No attempt is made here to argue whether these principles are ultimately right or wrong. That question isn't particularly productive at this stage of adoption, when most organizations are still figuring out the basics. What matters more is that these principles reliably describe how AI actually behaves when you place it in real systems, under real incentive structures, operated by real people with competing priorities and limited attention.

The agreement here is operational rather than ideological. You don't have to believe anything in particular about the future of AI to find these principles useful in the present.

A recurring pattern of failure

Across industries and domains and organizational contexts, the same basic pattern keeps appearing.

A system gets introduced because someone believes it will save time. It gets trusted earlier than it probably should be, before anyone has developed a feel for its limitations. Its output starts being treated as judgment rather than suggestion. Its errors get discovered downstream, often by someone who wasn't involved in the original decision to use it. And then responsibility becomes diffuse—hard to assign, easy to deflect, uncomfortable to discuss.

This pattern doesn't repeat because people fundamentally misunderstand AI at some conceptual level, or because they haven't read the right explainers. It repeats because the rules governing the interaction remain implicit, assumed rather than stated, felt rather than formalized. Principles are a way of surfacing those rules before the pattern completes itself again.

Each principle in this series isolates a recurring failure mode—not to assign blame after the fact, but to make the constraint visible before it matters.

Principles as boundary objects

These principles are deliberately scoped in a particular way.

They don't describe what AI might become someday, or speculate about artificial general intelligence, or prescribe policy positions that organizations should adopt. What they do instead is describe boundaries—what AI reliably does in practice, what it reliably doesn't do, and where human responsibility remains structurally unavoidable regardless of how sophisticated the technology becomes.

In that sense, they function as what organizational theorists call boundary objects. They can be shared across technical, managerial, and creative contexts without losing their meaning or their usefulness, precisely because they refer to observable behavior rather than contested ideology. A software engineer and a marketing director and a legal counsel can all use the same principle without having to first agree on deeper questions about what AI really is.

How this series is structured

Each article in this series takes on a single principle and nothing more.

It begins with a concrete episode or failure mode—something that actually happens, repeatedly, when AI gets deployed without sufficient reflection. The principle is then stated in a more formal way and examined through observation rather than explanation. The article ends without a neat thesis, returning agency to the reader through a question that lingers, a tension that remains unresolved, or a consequence that feels uncomfortably recognizable.

The goal isn't to persuade anyone of anything in particular. The goal is orientation—helping people figure out where they stand in relation to systems that are already reshaping how they work.

Why working with AI requires principles

AI systems scale in ways that almost nothing else does. They scale speed, and output volume, and variation, and the appearance of confidence. What they conspicuously do not scale is judgment. They can produce more, faster, across more domains—but the judgment about whether any of it is good, or true, or appropriate remains as human as it ever was.

Principles exist to prevent that scale from outrunning the responsibility that has to accompany it.

They're not guardrails imposed on the system from outside, by cautious managers or nervous regulators. They're properties of the system itself, features that become visible once you actually choose to work with it seriously rather than just marvel at what it can do.

This series is an attempt to make those properties visible before they make themselves known the hard way.

Sources

Christopher Mims, How to AI, Wall Street Journal Press.

Christopher Mims, Wall Street Journal technology columns on artificial intelligence adoption and practice.